Every time that we posted some of the charitable efforts we were undertaking across Zimbabwe with Citizens Initiative, we would receive messages from our patrons; “We have to do something about Binga.” This was a call to action and on 10 December 2020 we undertook a needs assessment trip to the district.

Binga is an underdeveloped and rural district that is tucked on the north-western corner of Zimbabwe. Most of its northern border is the largest man-made water reservoir in the world – Lake Kariba whose construction was more of a traumatic event than a blessing for the Tonga people who inhabited most of the submerged area. The dam was constructed between 1956 and 1959 by the Rhodesian colonial regime. Filling of the dam happened between 1959 and 1964 which resulted in forcible displacement of Tonga people from their homeland without compensation.

People who lived a few kilometers separated by the mighty Zambezi river but shared family and cultural ties were unilaterally separated and dumped further inland in both present day Zambia and Zimbabwe which were then known as Northern and Southern Rhodesia respectively. The productive land of the Gwembe valley which previously was the centerpiece of the Tonga economy was flooded and the inhabitants were moved further inland, mostly to unproductive arid land.

The colonial administration also created game parks and private safari establishments along the shores of Kariba which they valued more than the livelihood of the Tonga people. They even invested more in moving animals than resettling people as witnessed by the operation dubbed Operation Noah. This further pushed the Tonga people inland.

Although Kariba was built to be a hydroelectricity generation colossus, the people it displaced never really benefited from it.Most of Binga is extremely poor with little government investment in public infrastructure. There are gravel roads with most of them impassable.

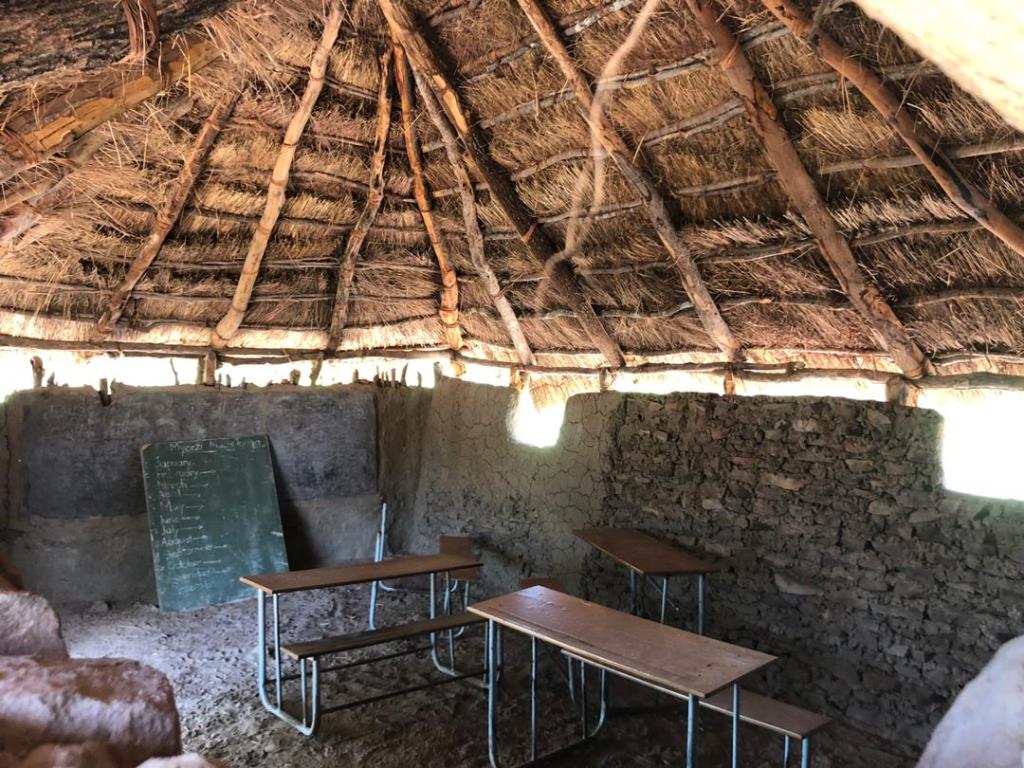

Our visit was mostly to assess the state of education infrastructure and see where we could be of help. The visit took us to Maacha, Kampandu, Gwatagwata & Masibinta. The state of what were called schools at these places was heartbreaking.

What was more devastating was listening to the stories of hopelessness from the communities especially around access to education. At Masibinta Secondary School, students learned outside, under a tree with no books. The previous year’s pass rate was 0%. The parents had been trying to build a school block from their meagre contribution but that effort was stalling.

We decided to crowdfund so we could help finish that classroom block. As per our modus, we used the local community to do most of the work. They were happy that at least some of the children would have a safe space to learn in.

In 2022 we got the diaspora grant from the International Organization For Migration to build, furnish and provide books to an underserved school in Zimbabwe. We went back to Masibinta and built one within 2 months.

The impact was real and instant. At Masibinta in 2023, the pass rate jumped from 0% to 13%. The following year it rose to 41.03%. This proved our working theory – academic outcomes are strongly tied to infrastructure.

It is this experience that got me asking questions. If a small investment of $65 000 had such a huge impact for the community, why is nobody focusing more on it? Why doesn’t the government invest in infrastructure? Everywhere you go, in those dusty roads you see 4×4 Landcruisers from NGOs operating in the area. Very few of them focus on developing infrastructure like water, schools and clinics. When you ask, most of them give you a long answer about “Building resilience and ….”

After much pondering you conclude, the people of Binga are on their own. Now, if they are on their own, what is it that they can do to pick themselves out of the bottomless pit? My compatriot Wellington Mahohoma observed that most of the families around Binga have honed the basket-weaving skill. In fact there are basket types that are specifically known as Binga Baskets.

We started looking into this and our research showed that in and around Binga people are making these baskets and are selling them for between $5-15. We scanned through some international markets and realized that most of these baskets are being sold at an average of $50. That is about five times what the artisans make in Zimbabwe.

The next part was to figure if the sellers were actually the makers. In more than 95% of the instances the sellers are not the makers and do not have any affiliation to the makers. What this means is that most of the value derived from selling these baskets does not really inure to the makers in Binga.

If the Binga makers were able to make $30 profit on a basket that would be a game changer. They would be able to afford basic necessities and send their children to school. It means a boost to local economy as more money circulates from the increased revenue.

Why then were the makers not choosing to sell internationally? The issue was access to the market. This is a remote area with no easy internet connectivity. Very few of the people even have electricity access. It becomes easier for them to go on the Bulawayo-Victoria Falls road and sell their wares to travelling tourists than to try and ship them to better markets.

What if we could bridge this gap? What if we could provide the opportunity to bulk ship their products and warehouse them closer to the market so that fulfillment happens faster? We have seen this work for Chinese companies like Temu. Why can’t we do the same for artisans, not just those from Binga or Zimbabwe alone but from different countries across the world?

This is how Tarooka.com was conceived. Our goal is to be a platform where makers profit from their skill without losing a chunk of their skin to middlemen. We believe that when you have talent, no matter where you are, you should be able to put food on your table.

Instead of feeling pity for the people of Binga and view them as a charity case, we are looking to flip the narrative. They are people who just haven’t had the opportunity to benefit from their hard work. There are many communities like that.

Regardless of where you are based, as long as you make things with your hands, we are there to help you put those products in front of the eyes of customers that appreciate the work you do. Opportunity matters!

You must be logged in to post a comment.